At this year’s Nest Insight conference our first panel looked at the day-to-day financial lives of defined contribution savers. During the session Dr Hayley James, a PhD researcher at The University of Manchester Institute for Collaborative Research on Ageing (MICRA), shared her research on individual decision making after auto enrolment into a workplace pension:

Some people aren’t saving enough through workplace pensions: it’s not clear how best to engage them

Automatic enrolment has been incredibly successful in encouraging participation in workplace pensions, with over 10 million people newly enrolled since the policy was introduced in 2012. Yet, most of those newly enrolled are saving at the minimum default contribution rate, which may not be enough to support the lifestyle they’re hoping for in retirement. This is further complicated by the fact that members do not appear to be engaging with financial incentives offered for greater contributions in the way expected. The question of how to encourage pension saving above the minimum levels has become a key debate in policy and industry.

Pension decisions are complex and varied

My research aimed to shed light on this issue by using qualitative research to provide a deeper understanding of the decisions made following automatic enrolment into workplace pensions. I conducted interviews with participants aged 20 to 49 years old who had already been through automatic enrolment and had decided to opt out, stick to defaults or increase their contributions, to understand how and why they had made this decision.

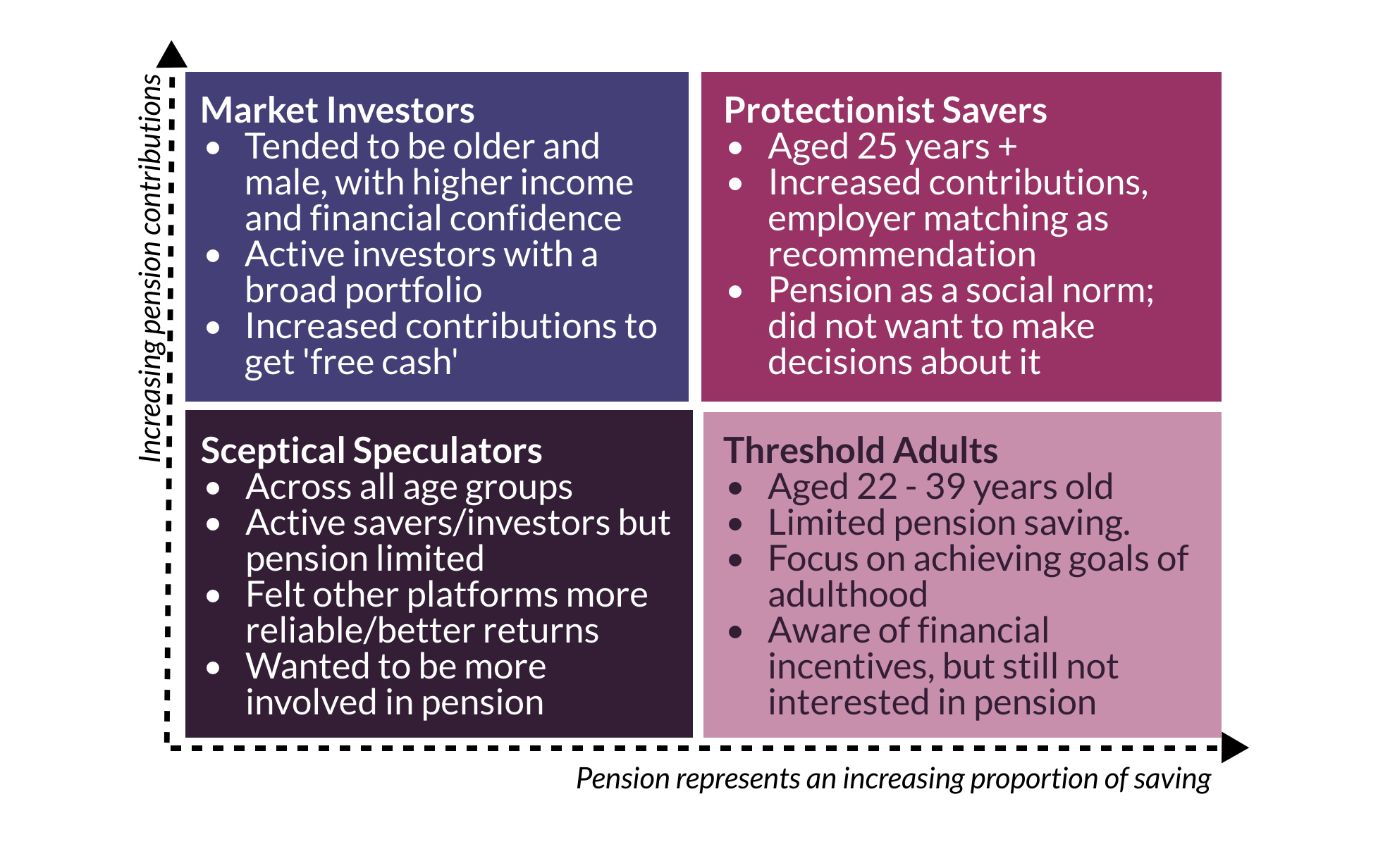

This research revealed the complexity of pension decision-making. The research identified four distinct approaches to pension decisions, which connected to how the individual understood their pension in the context of their everyday life experiences, including their life stage, relationships and other financial practices. This means that the approach could change over the course of their lives, for example, in relation to changes in life status such as career stage or parenthood. The four approaches are summarised below.

Solutions need to reflect these lived experiences

This variety of approaches means that there is no single solution to the question of engagement in pension saving. Different forms of support and intervention are needed which reflect the real lived experiences of pension savers. These solutions may not be solely policy driven, but might involve providers and employers working together, for example:

- The Threshold Adults: could benefit from interventions that recognise and support the challenges they face in this stage, for example, demonstrating that some goals, such as securing a place to live, are going to feel more important at this time. There is also an opportunity to use notifications at the employer-level which are triggered by a house move or having children, which may encourage Threshold Adults to think about pension saving at a time that feels right for them.

- The Protectionist Savers: are encouraged to save more by matched contributions, but they may need more clarity around the role of these incentives and the benefits of saving and investing through other means alongside the pension. This group responds well to shared platforms, such as events or FAQs, which connect to the social norm driving their pension saving.

- The Sceptical Speculators: may need more detailed and transparent information, not just about their scheme but pension saving in general, including charges and likely returns. Most importantly, this group wanted to participate more in their pension, so highlighted the possibilities to make decisions as well as providing feedback to their employer and provider may help them engage with pension saving.

- The Market Investors: were active savers and investors with a broad portfolio of products. They may benefit from tools including comparisons and calculators to support decision-making across the portfolio. The Market Investors may also need access to guidance or advice for all of their investments.

These approaches raise a concern about the model of workplace pension saving

The market investors, who were the most engaged group and probably behaved most like we expect pension participants to, seemed to have specific knowledge, access, social and economic capital that had aided them in developing this approach. This suggests that it is unlikely that the market investor approach could be successfully followed by everyone, which would affect the adequacy of pensions in the long-term. This is particularly important since the market investor group were mostly male, as gendered decision-making practices after automatic enrolment may reinforce the disadvantages women face in pension systems that do not take account of their real-life experiences, such as career breaks and lower pay. This concern about the role of engagement after automatic enrolment and its implications for pension outcomes deserves urgent attention from policymakers and industry groups.

Dr. Hayley James, PhD Researcher, University of Manchester Institute for Collaborative Research on Ageing (MICRA)

To find out more about MICRA and their research programme, visit: micra.manchester.ac.uk