Marge: You know, someday these kids will be out of the house

and you’ll regret not spending more time with them.

Homer: That’s a problem for future Homer.

Man, I don’t envy that guy.

(Excerpt from The Simpsons)

The future self can often feel like a different person and it’s sometimes hard to imagine that the struggles that will be faced in the future like declining health and insufficient retirement income might one day be our own. But the truth is that, like Homer, we’ll be stuck with the decisions that we make today.

The disconnect between the present and future self has been widely researched in behavioural sciences. People often say they want to save for retirement, but their future self never quite gets around to it. Automatic enrolment has been one of the big successes in this regard, sparing your future self the job of enrolling. Despite this, there is a need to increase the rate at which people save if they are to maintain the same quality of life in retirement as when working. One way to do this, is to increase the connection between the present and future self by making the future self more personally relevant.

Hal Hershfield conducted a series of studies whereby age progressed renderings of the future self were shown to participants prior to them making retirement saving decisions. Compared to avatars of a stranger, the personalised renderings resulted in significantly higher hypothetical contributions to retirement.

While Hershfield demonstrated an imaginative and engaging way to connect to the future self, it would be difficult to apply to all members of pension schemes in the UK. Instead, a method of increasing the connection without a significant additional administrational burden is needed. Sibila Marques and her colleagues used a questionnaire to increase connection with the future self in a study published in Portugal, which we recently attempted to replicate.

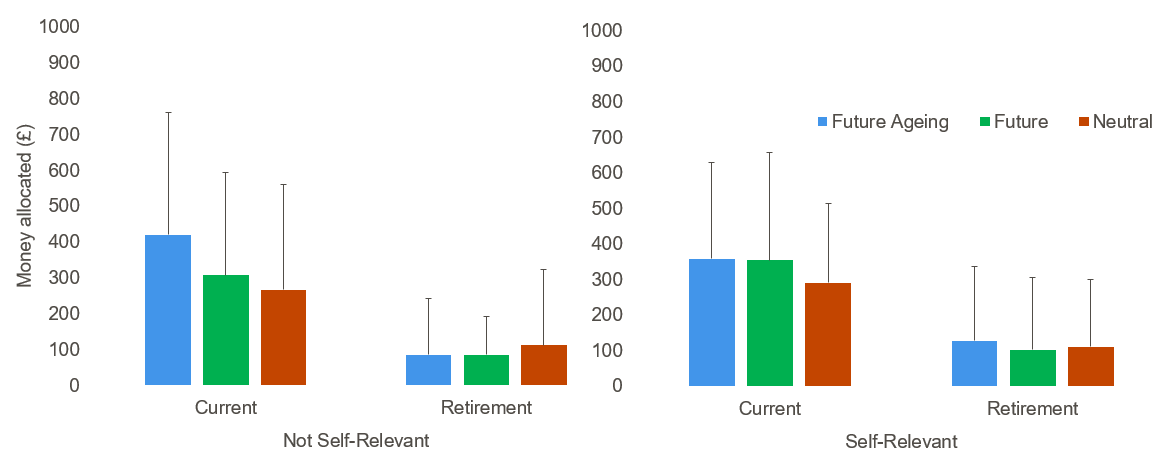

In both studies, participants saw either a questionnaire about the future (high future self-relevant) or not (low future self-relevance). They then viewed a fictional website which either primed future ageing, or which did not. They were then asked to allocate fictional money between five options, and while the options differed slightly between the studies, in both, some benefited the future self and others benefited the present self.

Marques demonstrated that those who are high in future self-relevance who saw these ageing primes save more for retirement than those low in future self-relevance. Yet our study, which was conducted in the UK, demonstrates no such effect.

Marques demonstrated that those who are high in future self-relevance who saw these ageing primes save more for retirement than those low in future self-relevance. Yet our study, which was conducted in the UK, demonstrates no such effect.

Ultimately, this difference in findings remind us that when applying behavioural science, just because an intervention works in one context doesn’t mean it will work in another or indeed in real life, where the demands on our money are complex and ever-changing. Yet, even though we might not know the best way to encourage it, there is little doubt that we should all be looking to the future to avoid the regret that we didn’t save enough for our future selves.

By Emma Stockdale and Michael Sanders

Emma Stockdale is a PhD student in the Department of Political Economy, and Michael Sanders is a Reader in Public Policy at the Policy Institute, both at King’s College London. Find out more: kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute

Read the full research paper here: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jasp.12673