Have you ever missed a bargain and regretted it? Maybe a good deal comes along after that but it’s not as good as the last offer and so you don’t take advantage of it. If this is you, you’re not alone – inaction inertia is when “one is not likely to act on an attractive opportunity after having bypassed an even more attractive opportunity” (Zeelenberg et al., 2006) and it’s common in retail, betting and even international negotiations. More recently, it’s been suggested that it can affect the way we save for retirement too.

All else constant, retirement saving represents a set of constantly worsening opportunities. That is, it will cost more money to start saving – or start saving more – at 30 than it would have done at 29. That’s because, the earlier people start to save, the more they can benefit from compound interest, employer matches and tax relief. But what happens if an individual is no longer ‘early’ in their career? If they feel they’ve missed out, are they less likely to increase their retirement contributions?

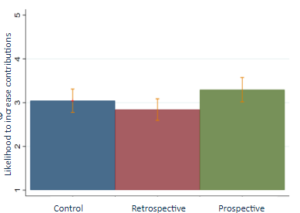

We recently ran a study which looked at just that. We showed participants a fictional letter from 10 years ago, informing them about the opportunity to increase their retirement contributions by £50 to live more comfortably in retirement. They were then told to imagine forgetting about the offer and not increasing their contributions. Next, we showed them one of three letters in the present:

- Letter one (control): which said that the increase would now be £215 to achieve the same wealth.

- Letter two (retrospective): which referred to the fact 10 years ago it would have been £50 but will now be £215 to achieve the same wealth.

- Letter three (prospective): which emphasised that it would cost £215 to increase now, but £510 to achieve the same wealth if increased in 10 years’ time.

Participants were then asked whether they would take up the current offer and increase their contributions.

The results indicate that those who saw the retrospective letter had significantly greater inaction inertia and were therefore less likely to increase their contributions than those in the prospective condition (Figure 1). This suggests that we should emphasise that not saving today will be a missed opportunity in the future rather than drawing attention to the past which only reminds us of the opportunity we’ve already missed.

Of course, the missed opportunity of retirement saving is often not as obvious as it was in our study. In reality, people find it hard to imagine the exponential growth of savings and therefore it’s sometimes difficult for people to tell that by not increasing their contributions they are missing out on ‘cheaper’ retirement saving compared to starting to save in the future. In the coming months we plan to look at this in more detail in the real-world to see whether inaction inertia really does occur in retirement saving.

By Emma Stockdale and Michael Sanders

Emma Stockdale is a PhD student in the Department of Political Economy, and Michael Sanders is a Reader in Public Policy at the Policy Institute, both at King’s College London. Find out more: kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute