Before the introduction of auto enrolment, saving for retirement was something that many people knew they should be doing but never got around to. But why? Behavioural economists believe there are a number of psychological barriers at play, including:

- Present bias – the tendency to overvalue immediate smaller rewards or pay-outs rather than waiting for a larger one in the future.

- Loss aversion –that people feel the impact of losses more than gains. In this instance, the money paid into a pension could feel like a ‘loss’ if it reduces an individual’s take-home pay.

- Procrastination and status quo bias – the habit of putting off or delaying completing a task, like signing up to save into a pension, and sticking to the current situation regardless of whether it’s the best or most rational thing to do.

A revolutionary solution

In America, renowned behavioural economist Shlomo Benartzi and Nobel laureate Richard Thaler came up with a behavioural intervention called Save More Tomorrow (SMarT). Designed to address these common obstacles to retirement saving, it comprises three elements to help make saving as easy and ‘painless’ as possible:

- To help avoid present bias, people are asked to commit to saving more in the future because it’s thought to be more attractive to do so later than to start now.

- To minimise loss aversion, people commit to increase their pension contributions when they receive future pay rises. This helps ensure that their take-home pay doesn’t decrease, making the savings feel like less of a ‘loss’.

- An employee who signs up is reassured that they can stop contributing at any point if the rising cost of contributions ever gets too much. But procrastination and status quo bias make it far less likely they’ll do so.

Adopting learnings from Save More Tomorrow

In the UK, auto enrolment has revolutionised the pension system. The policy’s design draws on a number of ideas from behavioural finance, including elements of SMarT. To date it has helped over 10 million people start saving for retirement.

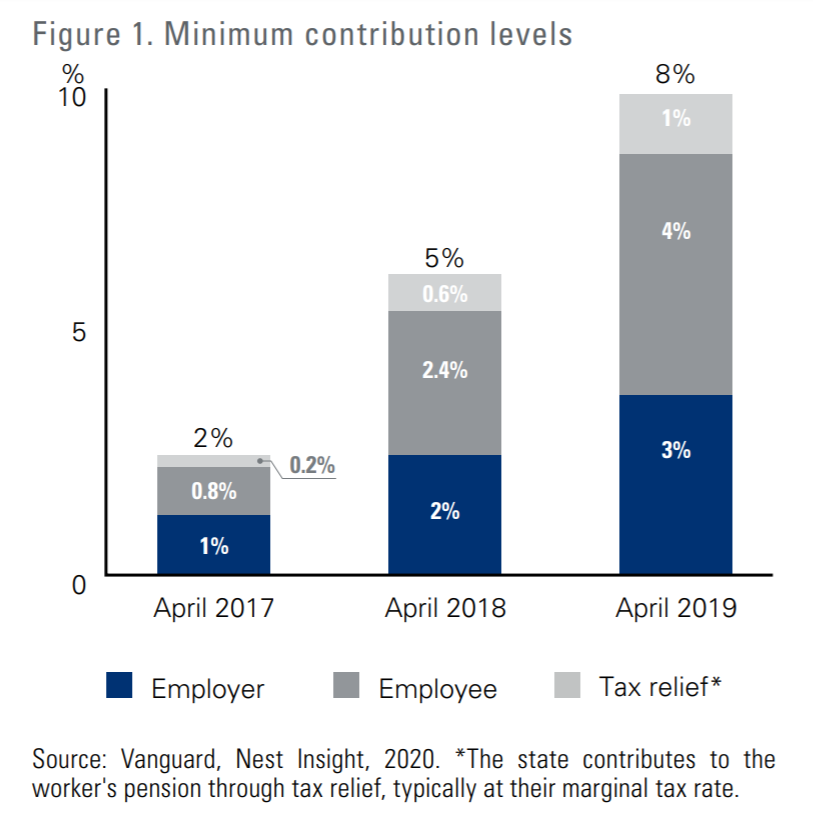

From 2012 onwards, workers across the country wer e automatically enrolled into a workplace pension with the right to ‘opt out’ within one month. They could also choose to stop saving at any point after that, an option known as ‘cessation’. The auto-escalation concept from SMarT was introduced through a process known as ‘phasing’. This gradual ramping-up of contributions was implemented to help smooth the experience of workers and employers. It began in April 2018, when the minimum total contribution level rose from 2% to 5%, and finally to 8% in April 2019 (see fig.1). Whilst these increases weren’t linked to individual pay rises, they did coincide with annual increases in the National Minimum Wage as well as in tax-free allowances, which would provide some cushioning for savers on lower and moderate incomes.

e automatically enrolled into a workplace pension with the right to ‘opt out’ within one month. They could also choose to stop saving at any point after that, an option known as ‘cessation’. The auto-escalation concept from SMarT was introduced through a process known as ‘phasing’. This gradual ramping-up of contributions was implemented to help smooth the experience of workers and employers. It began in April 2018, when the minimum total contribution level rose from 2% to 5%, and finally to 8% in April 2019 (see fig.1). Whilst these increases weren’t linked to individual pay rises, they did coincide with annual increases in the National Minimum Wage as well as in tax-free allowances, which would provide some cushioning for savers on lower and moderate incomes.

There are some important differences between the UK’s phasing approach, and the SMarT plans that inspired it:

- Participants didn’t choose the escalating contributions, they were defaulted into them. Still, the phasing approach relied on the same ‘softening’ effect of gradual increases, with the aim of making the cost more palatable.

- SMarT increases are usually timed to coincide with pay review dates, so that pay increases can offset the additional cost. It wasn’t feasible to time a nationwide programme of increases to the pay review dates of every UK employer. Instead, the increases were timed to happen in April, which allowed them to coincide with national changes to tax bands and the minimum wage.

- The UK increases were sharper than those seen in most SMarT programmes. Between March 2018 and April 2019, the employee contribution rose from 0.8% to 4%, net of tax relief – a five-fold increase in just over a year.

Given these differences, there was no guarantee the UK’s auto escalation approach would be as effective as those applied by many US employers.

Has phasing been successful in the UK?

Last week we published How the UK Saves: the effects of the second savings rate increase (PDF) with our strategic partner, Vanguard. This supplement, and the report we similarly published last year, focusses on how Nest’s 9 million members behaved following an increase in minimum auto enrolment contributions.

In both instances, the increase in contributions had little to no impact on savers’ behaviours, with opt-out and cessation rates remaining very low. But what more can we learn by digging beneath the headline data?

Who’s responding and who isn’t?

We studied member-reported cessations across a range of factors, including how long people had been saving, their age, income, and gender. Our analysis revealed that the length of time an individual had been saving with Nest had by far the most significant impact on cessation rates, compared to other factors. Members with a scheme tenure of less than nine months were more likely to cease contributions in response to the change. In this case, it could be that for some of these individuals the relatively rapid increase from contributing no earnings to Nest, to contributing 4% of earnings, was too much of a savings shock.

Conversely, we observed that cessation becomes less likely as scheme tenure increases, suggesting a normalisation of retirement saving among workers. Through either inertia or inattentiveness, longer-tenured members appeared ambivalent to the higher overall savings rate.

People are most sensitive to the rate at the point of enrolment

Our analysis also looked at the behaviours of savers whose very first contribution to Nest was 8%, versus savers who had been previously enrolled at a lower rate and then, having stopped contributing through choice or leaving their employment, were enrolled again at the higher rate. We found that when people come in at the higher rate they’re a little more likely to opt out regardless of previous experience – the main thing was the savings rate when they joined.

A valuable case study

The success of auto enrolment in the UK, and the evidence shared through our How the UK Saves series, provides a valuable case study on how to help millions start saving for retirement.

Our latest research shines a light on auto enrolment’s smart design and provides strong evidence that even when a system doesn’t implement Save More Tomorrow at its most optimal design, the approach of automatically enrolling savers and slowly ramping up contributions is still highly effective.

Matthew Blakstad, Analysis Director, Nest Insight