As explained in a separate post, Nest Insight is working in partnership with Maastricht University to understand the beliefs and attitudes that motivate people to engage with their pensions. Researcher Wiebke Eberhardt used a large survey with Nest members to help understand the emotional and attitudinal dimensions the influence pension engagement and decision-making. Here, she explains her research and some compelling initial findings.

Encouraging people to prepare for retirement is one of our biggest challenges. Reforms of pension systems mean more choice, greater responsibility and higher investment risk for people. This shift puts individuals in the role of decision-makers, a role that many are not ready for. Some people actively seek out information about their retirement benefits, but most know very little about their pension and do not read information from pension providers. This leaves them unaware of their possible pension gaps – the difference what they will need in retirement and their actual level of savings. This can lead to severe consequences when they retire.

At this point, we do not know what drives certain people to gain information. Nor do we know how to encourage more individuals to take action. This is what we set out to explore in the current study.

We chose to focus on one specific behaviour: information seeking. This is the first step in the retirement planning process. Without information on their options or their expected retirement benefits, people cannot make sound decisions – on how much to save, when to retire, and so on. Pension providers are managing increasingly large and diverse populations of savers. With limited personal contact with participants, or knowledge of their circumstances, it can be difficult to understand their behaviour and choices, and to communicate effectively with them.

To help bridge this gap, we wanted to understand why some people search for information about their pensions while others do not.

The Retirement Belief Model

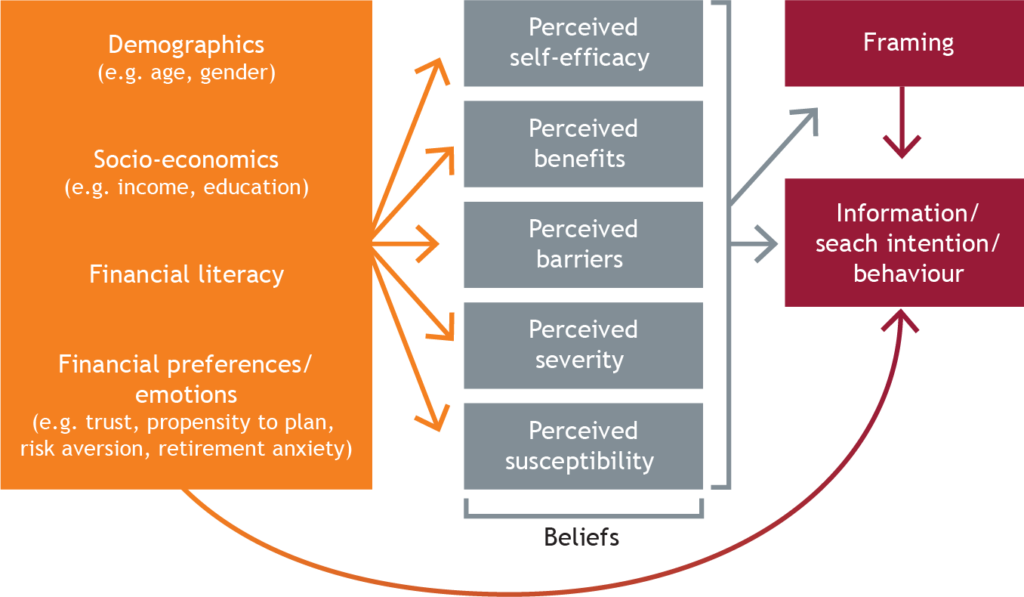

My team at Maastricht University developed a model to identify the most relevant beliefs surrounding pensions: the Retirement Belief Model (see Figure 1). According to this model, in order for individuals to search for information, they have to:

1. Believe that the consequences of not informing themselves are severe (severity)

2. Believe that they are at risk of experiencing an undesirable outcome such as a pension gap (susceptibility)

3. Think that the benefits of getting information outweigh the costs (benefits vs. barriers)

4. Feel that they are able to change their situation (self-efficacy).

Figure 1

We’d successfully tested this model before, with a Dutch pension provider. We used the model to segment this population and found three segments. Each segment had different beliefs that determined their intention to be active with their pensions.

In this Dutch study, though, we were only able to explore behavioural intentions. The population was also tended to be somewhat more affluent than the norm for the working population, as is normal among corporate pension arrangements. By working with Nest Insight, we were able to overcome both of these constraints.

In autumn 2016, we sent out the Retirement Belief Model survey to almost 100,000 Nest members. This included those who had registered on the Nest website to view their accounts, and those who hadn’t. 1,349 completed the questionnaire, and of these we have complete data on age, gender, income and children for 1,156 members. Using a combination of people’s statement, and the administrative data held on them by Nest, we made comparisons based on five different characteristics:

- whether members are already informed about their pension

- whether they intend to search for information in the near future (both measured by survey questions)

- whether they have registered, made additional contributions or switched funds (all indicated by administrative data).

After initial analyses, I can report on three main findings:

1. Demographic characteristics alone were not enough to tell us who would or wouldn’t take action

It’s only when we took into account people’s beliefs, and other psychological factors such as emotions and trust, that we were able to see why some took action. For instance members were significantly more likely to register on the website if they:

- saw significant benefits of seeking information search, such as peace of mind

- had a high degree of self-efficacy – for instance they knew where to look for information and how to use it

- had high levels of trust in Nest and positive emotions towards pensions and financial decision making.

For information search, perceived benefits and self-efficacy were the most important beliefs, while people who felt that they were at risk (high susceptibility) often shied away from taking action.

2. There were, however, some behavioural differences between different demographic groups

Members with higher income were more likely to make additional contributions and switch funds. Older members were more likely to register online, though this is the only behaviour that was affected by age. The factor that seemed to make a significant difference was life events. Members who were married, for instance:

- were more likely to have informed themselves about their pensions

- had stronger intentions to find out information

- saw more benefits in seeking information, and lower barriers to doing so

- experienced lower levels of retirement anxiety and less negative emotions towards pensions and finance

- had more trust in the financial industry.

Likewise, members with children:

- were more likely to have informed themselves

- had higher information search intentions and a higher propensity to plan

- saw more benefits in seeking information

- had less negative emotions towards pensions and finance

- had more trust in the financial industry and Nest.

3. The role of different beliefs and psychographic factors varies from person to person

We used Pathmox, a technique based on a branching tree structure, to divide our population into five segments. At the first step, we used only demographic characteristics to form these segments. After this, we applied the Retirement Belief Model. The Pathmox algorithm identified three characteristics that created the greatest differences between segments:

- being registered

- income

- marital status

- having children.

Using these variables, we create five distinct segments:

- The first segment is registered and has a gross annual income of more than £35,001. This segment is the second oldest, with a mean age of 46.7 years. 53% are men. Key beliefs were:

- perceived benefits

- perceived severity (how bad it is not to save enough for your pension).

- The second segment is registered, with income below £35,001. Mean age is 43.5 years and half the members in this segment are women. Key beliefs were:

- perceived benefits

- self-efficacy.

- The third segment is unregistered and married. The mean age is 44.8 years and 54% are female. Median income is £20,001-£25,000. The key belief was:

- perceived benefits.

- The fourth segment is also unregistered. They have one or more children, though 60% are single or divorced. This segment is the oldest, with a mean age of 47 years. 65% are women. Median income is £15,001-£20,000. Key beliefs were:

- self-efficacy (the most important positive driver of information search)

- perceived benefits.

- The fifth segment is unregistered and has no children. This segment is the youngest, with a mean age of 32.1 years. 60% are women and median income is £15,001-£20,000. Key beliefs were:

- self-efficacy.

These findings support our expectation that heterogeneity of savers matters. They underline the importance of taking a different approach to different groups of members. Pension populations are diverse, and they face different barriers and drivers. Communication should be tailored to their needs, and the insights from this research will help us do this. More research is, however, needed, to shape and test these tailored communications. Working with NEST Insight, we’re continuing to develop new way of engaging members and helping them work towards a better income in retirement.

About the author:

Wiebke Eberhardt is a doctoral researcher at the department of Finance and the department of Marketing and Supply Chain Management at Maastricht University. She is currently a visiting researcher at Leeds University Business School and is working closely with the Centre for Decision Research. Wiebke is also a member of the Pension Communication group at Maastricht University and junior fellow at Netspar. In 2015 she was awarded the Investments and Pensions Europe Pensions Scholarship Fund research grant to support her research on DC pension communication.